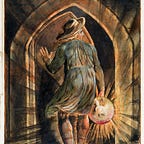

“Furure Shock” is not the issue, getting from Past to Present is shock enough

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things…partly from the incredulity of mankind, who do not truly believe in anything new until they have had actual experience of it.”

Niccolo Machiavelli

“Within a millisecond the bat presses the ball

the bullet enters and exits the target

the rock plunges into the pond

Within a nanosecond balls, bullets and droplets are motionless”

James Gleich, “Faster”

When we look back on our professional lives most of us can recall at least a few things with which we are less than happy. That’s certainly true for me. When I was a young man, working for a large management consulting firm, I was asked to lead a “change management” effort for a very large company. That meant asking a large number of people to change the way they worked. Early on it was quite easy to categorize employees, as it related to the changes we asked of them, into three groups:

- Supporters — 20%

- Resistors — 60%

- Saboteurs — 20%

The categories pretty much speak for themselves. We attempted to work with the change related issues of individuals in each group accordingly.

I’ll be the first to admit that our change management efforts failed. The reasons for the failure are not the point of this article and really not the point of my unhappiness. What I am most unhappy about is the lack of knowledge we had related to the reasons 80% or so of employees were predisposed to resistant change and the threat that posed to our change management efforts.

Even though, as management consultants, we had a bevy of reasons why we understood change management and could manage related projects, now that I look back on it, we really didn’t. We didn’t understand the depth of the mental and psychological issues associated with the resistance most human beings exhibit when asked to change. Those issues are prevalent in our lives today and because of the technology available to all of us much more acute. It’s in all of our interests to give change related stress some careful thought.

Mobile phones have become a modern day clarion of change. We compulsively check our email because we’re unsure of the change the next message will bring. Will it be for leisure/amusement, an overdue bill, a “to do”, a query… something we need to do now, something life-changing, something irrelevant. That uncertainty wreaks havoc with our rapid perceptual categorization system. Neuroscientist, like Hadley Bergstrom, advise us that the demands of new information and related uncertainty leads to decision overload and causes stress.

As I learned during my management consulting effort, new information creates disorder and, even if for a temporary period of time, disorder is stressful. Physicists have worked with disorder for quite some time. They describe it as Ludwig Boltzmann did in the 19th century. According to Boltzmann”

“whenever heat is added to a working substance, the rest position of molecules will be pushed apart, the body will expand, and this will create more molar-disordered distributions and arrangements of molecules. These disordered arrangements, subsequently, correlate, via probability arguments, to an increase in the measure of entropy”.

Disorder, related to the receipt of new information, can be illustrated the way physicists think of entropy.

Think of being presented with new information as heat being added to a “working substance”. When that happens the “rest position” older information assumed in our brain is disturbed. To quote Boltzmann, it is “pushed apart, and creates disordered distributions and arrangements of molecules”. Except, in the case of the human brain it’s not molecules being disturbed, it’s connections among neurons.

The average human brain has about 100 billion neurons (or nerve cells). Each neuron may be connected to up to 10,000 other neurons, passing signals to each other via as many as 1,000 trillion synaptic connections, equivalent by some estimates to a computer with a 1 trillion bit per second processor. Estimates of the human brain’s memory capacity vary wildly from 1 to 1,000 terabytes (for comparison, the 19 million volumes in the US Library of Congress represents about 10 terabytes of data.

Each individual neuron can form thousands of links with other neurons, giving a typical brain well over 100 trillion synapses (up to 1,000 trillion, by some estimates). It is within those synapses or links among neurons that our accumulated knowledge is stored. Functionally related neurons connect to each other to form neural networks (also known as neural nets or assemblies). The connections among neurons are not static, though, as our knowledge is updated connections change and it is that disruption or disorder in our neurons that is how we “experience” change.

The more signals sent between neurons, the stronger the connection grows (technically, the amplitude of the post-synaptic neuron’s response increases), and so, with each new experience and each remembered event or fact, the brain slightly re-wires its physical structure. As we process new information we experience some degree of re-wiring in our brain. That “re-wiring” or change creates some degree of disorder or entropy. Feelings arise from the disorder and sometimes those are uncomfortable feelings, human beings generally like to avoid.

Even an “aha!” moment — when something suddenly becomes clear — doesn’t come out of nowhere. Instead, it is the result of a steady accumulation of information. That’s because adding new information opens up memories associated with the task. Once those memory neurons are active, they form new connections, explains Dr. Bergstrom, of the National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Bergstrom says humans can form stronger connections within an existing network. Over time, our level of understanding increases until we suddenly “get” it. Now into this sophisticated system of information management we were are adding speed. Speed like our species has never known

Whether it’s social media or scientific journals, the half-life of knowledge is changing at an increasingly rapid rate, so much that our neurological information management system is being asked to accommodate change within a nanosecond like the balls, bullets and droplets James Gleich describes as becoming motionless within a nanosecond. Individuals that suffer from change induced stress need a place where they can cleanse themselves of old information and move-on to new information. In doing so they’ll be relieved of the stress of having to experience, sometimes, debilitating change and make a healthy move to the future.

We’re all being required to do more. In the past travel agents made our airline and rail reservations, salespeople helped us find what we were looking for in shops and professional typists or secretaries helped busy people with their correspondence. Now we do most of those things ourselves which we call “multitasking” but we’re not very good at it. And we’re attempting to multitask at a faster rate.

Asking the brain to shift attention from one activity to another causes the prefrontal cortex and striatum to burn up oxygenated glucose, the same fuel they need to stay on task. According to Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at MIT, “When people think they’re multitasking, they’re actually just switching from one task to another very rapidly. And every time they do, there’s a cognitive cost in doing so.” … Multitasking has been found to increase the production of the stress hormone cortisol as well as the fight-or-flight hormone adrenaline, which can overstimulate your brain and cause mental fog or scrambled thinking. Make no mistake: email-, Facebook- and Twitter-checking constitute a neural addiction.

Change, resulting from the frequency with which new information becomes available, is accelerating and because change and time are essentially the same (i.e. time is the rate at which change occurs) it feels like time is accelerating as well. It’s the sometimes never ending stream of new information that’s causing change. The flood of new information produces the “feeling” of time accelerating which is the real source of change induced stress.

Russ Poldrack, a neuroscientist at Stanford, found that learning information while multitasking causes the new information to go to the wrong part of the brain. Forgetting or disremembering is the apparent loss or modification of information already encoded and stored in an individual’s long-term memory. It is a spontaneous or gradual process in which old memories are unable to be recalled from memory storage and while none of us like to “forget anything” forgetting helps to reconcile the storage of new information with old knowledge . As a consequence forgetfulness may be on the rise because of all of the new information we are being asked to manage.

Forgetting arises when other competing traces interfere with retrieval and inhibitory control mechanisms are engaged to suppress the distraction they cause. Repeatedly retrieving target memories suppressed cortical (cerebral cortex.) patterns unique to competitors. Remembering a past experience can, surprisingly, cause forgetting.

I no longer have the self-assurance I once did , regarding our ability to “manage” change, especially in a world of instantaneous information. Human brains need time to absorb and process information. Gone from the incessant pace of our society is the time required to sit and ruminate. One sure way to rob our brains’ ability to retain information is to break away from a high-information environment (such as reading for a class) to another high-information environment (such as surfing the internet or checking email). Maybe we could curb the ever expanding physical density of America if more people would learn that movement is a low-information environment.

Individuals that suffer from change induced stress need a place where they can receive new information without experiencing the, sometimes, debilitating change, caused by new information replacing old information. Alvin Toffler once wrote about issues related to “Future Shock“. In the future, we’ll just need a place from which we can make a healthy move to the present.

Notes:

- http://www.human-memory.net/brain_neurons.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/18/modern-world-bad-for-brain-daniel-j-levitin-organized-mind-information-overload

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/creativity-without-borders/201405/the-myth-multitasking

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/18/modern-world-bad-for-brain-daniel-j-levitin-organized-mind-information-overload

- Joanne Cantor, Conquer CyberOverload: Get More Done, Boost Your Creativity, and Reduce Stress 2010

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgetting#cite_note-5

Originally published at neutec.wordpress.com on October 29, 2017.